The Pike expedition’s adventures in the modern state of Colorado proved to be the crucible that tested their mental resolve and physical stamina as no other segment of the journey. Within its borders, events conspired on several occasions to bring them to near disaster, yet the time they were in Colorado also proved in many ways to be their finest hour. Appropriately, Colorado also contains Pikes Peak, a monument grand enough to recognize the magnitude of their achievements.

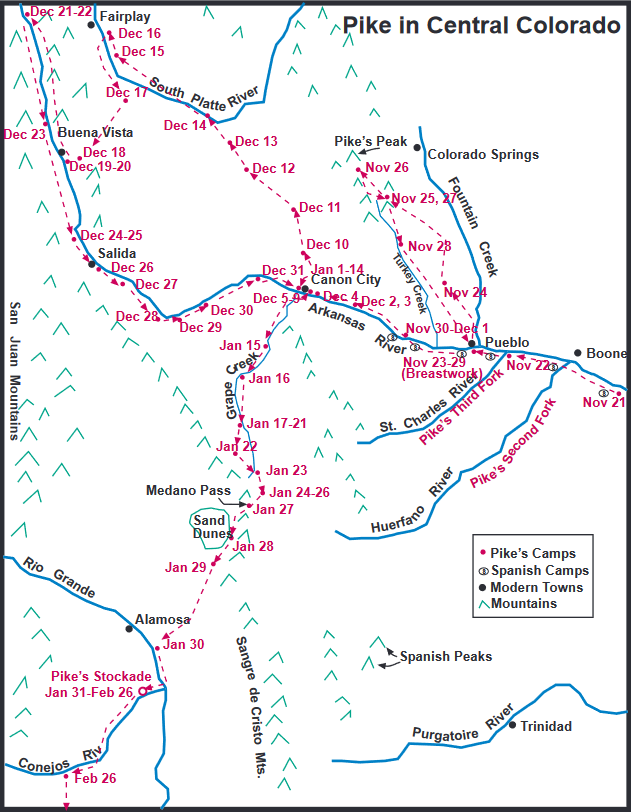

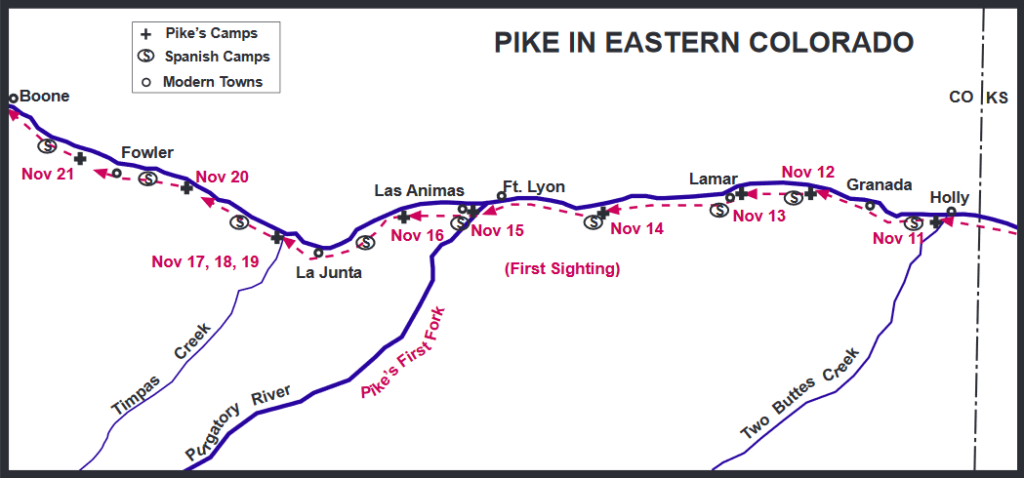

The expedition entered the state on November 11, 1806, and made their first Colorado camp near the present-day town of Holly. Pike was still seeking the source of the Arkansas River, and was pressing ever westward, following both its sandy valley floor and the trail of a large Spanish force under Lt. Facundo Melgares. The Americans had seen Spanish and Indian campsites of considerable size recently, although Pike’s journal indicated that they had not sighted a soul for quite some time. That, however, was soon to take a dramatic turn.

On that same crisp November day, Pike made a decision that was to have momentous consequences. “Finding the impossibility of performing the voyage in the time proposed,” he confided to his journal, “I determined to spare no pains to accomplish every object even it should oblige me to spend another winter in the desert.” In the pursuit of “every object” of his voyage, he would soon discover that the plains of his “desert” would soon rise up to become the Rockies, and the last whispers of Indian Summer would soon turn into the frigid blasts of a Colorado winter—events formidable enough in their own right without the fact that in order to cut down on excess baggage, Pike had ordered all winter uniforms be left back in Missouri.

A Glimpse at Immortality

Pike’s party was forced from the river bottom up these bluffs. From this elevation a short distance from here, he first sighted what would become Pikes Peak.

The heretofore uninhabited landscape soon changed as well. On the 12th, Pike’s hunters cut a trail with very fresh signs of Indians, and one was spotted briefly in the distance. But three days later, an even more significant sighting was made.

On Saturday, November 15, the expedition encountered bluffs in a bend of the Arkansas that forced them out of its valley on the south side of the river and up onto the prairie above. As they made their way along this higher ground, a “small blue cloud” on the horizon caught Pike’s eye. A glance through his spyglass heightened his suspicion that the cloud was actually a mountain.

Gazing west from this spot, Pike first saw a hint of the “ Grand Peak.” Today’s atmospheric conditions make such sightings rare.

Thirty minutes later, his suspicion was confirmed as a snow-covered peak materialized from the prairie floor, followed later by the outlines of the outliers of the front range of the Rockies. Pike always referred to the mountain he first saw as the “Grand Peak,” or the “blue mountain,” but later, others would formally name it in honor of the first U.S. citizen to lay eyes on it: Pikes Peak. While its soaring mass seemed deceptively close on that November day, he was still some 120 miles from the mountain that would immortalize his name.

An Unwelcome Welcoming Committee

The subject of mortality may have loomed a bit larger a week later, as the expedition’s westward travels uncovered increasingly more frequent and recent signs of Indian activity, and the prospect of an eventual meeting brought both feelings of anticipation and worry. On November 22, the probable source of all the signs suddenly appeared in the form of sixty Pawnee warriors, who rushed the expedition from out of the brush along the river.

The Pawnees were a war party returning from an unsuccessful campaign against the Comanches, and were in a sour mood. An official parlay ceremony was arranged and Pike passed out gifts, but a number of the warriors wanted more. As the situation became increasingly tense, Pike decided to pack up and leave, but as they mounted up, the Indians mobbed them, snatching items from the soldiers and their packs. Only when threats were made to open fire on them did the warriors disengage and vanish back into the brush. It had been a close call, and with only sixteen men in Pike’s party confronting sixty Pawnee, a shooting incident would have resulted in a bloodbath.

Pike Challenges the Mountain

By November 23, Pike felt that he was close enough to the Grand Peak to attempt an ascent. The Arkansas appeared to be dividing into smaller streams, and it was felt that once atop a lofty peak, the countryside and its rivers could be traced for great distances.

In the middle of what is today’s city of Pueblo the expedition built a defensive stockade of logs. From this base camp, a small party would make the ascent, while the rest would remain to guard the horses and supplies. Pike, fooled by the optical illusions of distances on the western plains, estimated that the march to the base of the mountain and its ascent could be accomplished in two days.

The four-man climbing party, which consisted of Pike, Dr. Robinson, and two privates, left camp on November 24 for the ascent. Due to Pike’s distance miscalculations, the party took two days instead of one to reach the base of the mountains. The climb began on the morning of the 26th, but continuing miscalculations of distance and deteriorating weather left them only partway to the summit by nightfall. The following morning, after battling 22-degree temperatures and waist-deep snow, the party arrived at the summit, where they were treated to a spectacular view of oceans of clouds below them and a panoramic blue sky above. Their vista also revealed that due to their obscured view of the peaks from the valley floor the previous day, they had ascended the wrong peak, and were standing atop 11,499 ft. Mt. Rosa. The “Grand Peak” still lay some fifteen miles away. Chastened by the exertions of their climb, Pike gave up the idea of a second assault, and the group returned to their stockade base camp on November 29. Pike’s assault on Mt. Rosa was the first known successful alpine ascent of a mountain by a person of European descent in North America. Click Here for a detailed examination of the controversy surrounding his feat.

The four-man climbing party, which consisted of Pike, Dr. Robinson, and two privates, left camp on November 24 for the ascent. Due to Pike’s distance miscalculations, the party took two days instead of one to reach the base of the mountains. The climb began on the morning of the 26th, but continuing miscalculations of distance and deteriorating weather left them only partway to the summit by nightfall. The following morning, after battling 22-degree temperatures and waist-deep snow, the party arrived at the summit, where they were treated to a spectacular view of oceans of clouds below them and a panoramic blue sky above. Their vista also revealed that due to their obscured view of the peaks from the valley floor the previous day, they had ascended the wrong peak, and were standing atop 11,499 ft. Mt. Rosa. The “Grand Peak” still lay some fifteen miles away. Chastened by the exertions of their climb, Pike gave up the idea of a second assault, and the group returned to their stockade base camp on November 29. Pike’s assault on Mt. Rosa was the first known successful alpine ascent of a mountain by a person of European descent in North America. Click Here for a detailed examination of the controversy surrounding his feat.

A Costly Error

With the question of the Arkansas’ source unanswered by the view from the climb, the party abandoned their stockade camp on November 30 and pressed west.

This view of the Arkansas south of the Royal Gorge gave Pike little hint of what was in store for him ahead.

Winter was now turning its full force on them, with snow and bitter temperatures becoming the norm. By December 5, they were near the entrance of the spectacular Royal Gorge, near present day Canon City. Here Pike spent several days trying to determine which of several streams in the area was the main branch of the Arkansas. His patrols reported that the stream entering the gorge, which they correctly took to be the main channel, appeared to play out. The low flow of water in 1806 may have simply been due to a previous dry season, but it led Pike to erroneously conclude that he had finally reached the river’s source—a decision that would have a significant bearing on events to come.

Since he believed he had finally discovered the headwaters of the Arkansas, Pike now turned his attentions to the source of the Red River, which was presumed to lie somewhere to the southwest of their current position. But instead of heading in that direction, Pike compounded his Arkansas headwaters error by heading north, following what he thought to be the trail left by Melgares, whose experience in the region presumably would cause him to head by the easiest route to the Red on his way back to New Mexico. Unfortunately, Pike wasn’t following a Spanish trail, but mistakenly followed an old Indian trail that was, in fact, leading him away from the object of his quest.

By December 14, Pike’s northward journey struck a river, but to his surprise, it was flowing to the northeast and was obviously not the Red, whose course was presumed to flow southwest. Pike had actually discovered the headwaters of the South Platte, a significant tributary of the Missouri River. While this was an important discovery, Pike surmised that he was now too far east and north to find the Red, and redirected his course accordingly. In actuality, he would have had to head south-southeast to have ever had a chance of finding it.

A Stunning Surprise

Pike’s error in assuming that the headwaters of the Arkansas stopped at the entrance to Royal Gorge now returned to haunt him. The Arkansas had not ended there, but had simply disappeared into the depths of the gorge, an illusion heightened by the unusually low seasonal water level and the fact that winter had partially locked the rest in ice. Unknown to the explorers, the river continued north for over one hundred miles to its source. On December 18, the expedition encountered the river again some seventy miles above the entrance of the gorge near present-day Buena Vista. Believing that the Arkansas ended back at the gorge, Pike assumed that he had at last struck the Red.

The expedition now turned upstream to find the source of the new river. By December 22, Pike had arrived at a high point where the panoramic view of the river ahead convinced him that he was looking at the origins of the (supposed) Red River as it entered some mountains near the modern town of Leadville.

The party then turned downstream, and north of today’s Salida spent a frigid Christmas Day. The ill-clothed explorers were now suffering in the grip of the depths of winter, and Pike’s journal entry for the date vividly relates their plight:

“Here I must take the liberty of observing that in this situation, the hardships and privations we underwent, were on this day brought more fully to our mind. Having been accustomed to some degree of relaxation, and extra enjoyments; but here 800 miles from the frontiers of our country, in the most inclement season of the year; not one person clothed for the winter, many without blankets, (having been obliged to cut them up for socks) and now laying down at night on the snow or wet ground; one side burning whilst the other was pierced with the cold wind: this was in part the situation of the party whilst some were endeavoring to make a substitute of raw buffalo hide for shoes &c. I will not speak of diet, as I conceive that to be beneath the serious consideration of a man on a voyage of such nature. We spent the day as agreeably as could be expected from men in our situation.”

The Arkansas as it heads into the north entrance of Royal Gorge.

An even less agreeable surprise was revealed to the expedition a few days later. As their southward trek downriver brought them to the northern entrance of the Royal Gorge on December 28, they little realized that they were approaching the very point that they left on December 9.

Pike broke the party into detachments with various missions, and some of them struggled down the treacherous landscape for nearly twelve days before finally assembling at its south entrance.

The realization that he had mistaken the northern reaches of the Arkansas for the Red River dawned on Pike even before the party regrouped in today’s Cañon City.

Pike and part of his party climbed up this sheer crevice and out of the gorge with virtually no modern moutaineering gear!

On December 31, he had climbed up the sheer sides of the Royal Gorge canyon and onto the north rim. From an elevated spot a day later, Pike was stunned to recognize landmarks to the south that he had seen nearly a month before!

A Perilous Decision

On January 9, Pike confided to his journal that he now felt “at a considerable loss how to proceed.” If he was not lost, he was perilously close to it. After considering his options, however, he decided that same day on a course of action. The expedition’s horses, which were now unfit for an extended trip, as well as any unnecessary supplies, would be left in charge of two men at a log stockade they built at their present campsite. The fourteen remaining men would carry crucial supplies on their backs, and set out on foot to seek the Red River. Pike estimated that each man’s burden, with firearm and pack, averaged some seventy pounds. The expedition would be afoot in an uncharted wilderness, weighted down with equipment, inadequately clothed, and in the depth of a Rocky Mountain winter. They left camp on January 14, 1807, under conditions that could well prove to be a recipe for disaster.

The planned route was to head up a southern tributary of the Arkansas called Grape Creek, cross the Sangre de Cristo mountains to the west, and locate the Red, which he imagined to lie somewhere beyond their snow-covered peaks.

In the Jaws of Catastrophe

Within three days the trekkers were in trouble and immobilized, nine of the fourteen men—including those detailed to do the hunting—having frostbitten their feet while fording Grape Creek. Pike and Dr. Robinson, whose feet were still sound, struggled for two days to find game to feed the crippled party, finally killing a buffalo on January 19. By then, most of the men had not eaten for four days. Pike himself nearly fainted from hunger as he struggled into camp with his load of meat.

On January 21, Pike made a heart-wrenching decision. Realizing that they could tarry no longer in their present inhospitable surroundings, he left two of his men crippled by frostbite with as many provisions as could be spared and a promise to rescue them later, and pressed on. The march south through what appropriately enough today is known as the Wet Mountain Valley, and along the front of the Sangre de Cristos was now becoming a race to find a pass. They were now battling through snow over two feet deep, battered by snowstorms, and their critical buffalo food source had apparently left the area.

On January 24, the expedition attempted their first traverse of a promising pass, only to be turned back by deepening snows. Even the normally optimistic Pike was shaken, recording in his journal that “for the first time in the voyage, found myself discouraged.” Worse, for the first time in the trip, one of the privates openly complained of his condition in a way that their commander found “seditious” and “mutinous.” While this appears to have been an isolated case that Pike was quick to quell, it was indicative of the deepening stress brought on by gnawing hunger and physical strain. A break in the weather of the 24th led to the killing of four buffalo for much needed food, but Pike admitted in his journal that if the snowstorms of the last few days had lasted another day, they would all have probably perished.

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire

This latest brush with disaster made avoiding a similar incident all the more crucial, and necessitated leaving yet another frostbitten member behind with supplies when the party moved out on January 27. Later in the day, they discovered an ever-widening stream flowing west. With hope renewed, the party followed what they hailed as the waters of the Red River, and made their camp that evening at the entrance of a promising pass through the mountains. The next day, the stream led them through today’s Medano Pass, an easy passage through the mountains into the San Luis Valley.

Medano Pass as seen from Pike’s Stockade appears as a deep notch in the Sangre de Cristos. The Sand dunes are the light strip at the base of the mountains to the left of the pass.

As the beleaguered explorers stood at the western exit of the pass, they were greeted by a unique landscape: the ocean of sand that comprises today’s Great Sand Dunes National Monument. They spent the rest of the day angling south between the dunes and the western face of the mountains. At their camp that night, Pike climbed one of the towering dunes and turned his spyglass west. His heart must have raced when it revealed a large river, flowing southwest, in the manner of the Red. By January 30, they were standing on its banks. What they did not realize was that they were on the banks of the Rio Grande; the Red was still several hundred miles to the southeast. He had also crossed into land controlled by imperial Spain, and was now a trespasser in the territory controlled by Spanish New Mexico.

There has been a lively academic debate about whether Pike mistakenly or deliberately wandered into Spanish territory. Had he made an honest error in mistaking the Rio Grande (generally held to be in Spanish territory) for the Red River (claimed by the U.S. as a part of the Louisiana Purchase), or had he deliberately committed trespass to spy on the Spanish as part of his orders from General Wilkinson? Pike’s journal makes no mention at this time of his fears should he be trespassing, but the rescue of his men stranded between the Arkansas stockade and his present position seems to have weighed heavily on his mind, and he developed his plans accordingly.

A Home on the Red River?

The expedition moved downriver to locate a stand of timber suitable for building a substantial stockade for a base camp. On January 31, they decided on a location five miles up the Conejos River, a western tributary of the Rio Grande. To protect them from against the “insolence, cupidity, and barbarity” of any nearby Indians, they immediately set to work on the stockade. Constructed of heavy logs and complete with a defensive moat, it was built on a square plan, with walls approximately thirty-six feet to a side, and twelve feet high.

This modern reproduction of the stockade now stands on the site.

By February 7, the works were apparently complete enough to allow Pike to order a five-man detail back through the mountains to retrieve the frostbitten men. That same day, Dr. Robinson took his leave of the group and headed in the direction of Santa Fe, where he reportedly was to act as a business agent for a U.S. merchant with claims on persons residing there.

Nine days later, Santa Fe came calling on the Conejos in the form of two armed horsemen. While Pike and a companion were out hunting, they met a Spanish dragoon and his Indian companion from Santa Fe. After spending the night at the stockade, they departed on February 17 without venturing the news to its garrison that their stronghold was on the Rio Grande.

By the 18th, the rescue party had arrived back with one of the frostbitten men, but reported that the two more distant ones were still unable to travel. The following day, a second party left to make the 180-mile trip to the Arkansas stockade, fetch its men, horses, and supplies, and pick up the two cripples on the way back.

When the two Spaniards left to return to Santa Fe on the 17th, Pike sent word to New Mexican Governor Joaquín Alencaster that should he wish to discuss the expedition’s presence on the frontier, he would welcome a visit from the governor’s emissary. The invitation was answered on February 26, when fifty mounted dragoons and fifty armed militiamen arrived at the stockade.

In the ensuing conversation with their officers, Pike was informed that Governor Alencaster had extended an offer to conduct them to the headwaters of the Red River, since they had “missed their route.” Grasping the implications of this, Pike demanded, “is this not the Red River?” “No sir!” the Spanish commander retorted, “the Rio del Norte.” Further, the governor wished for Pike and his men to accompany his soldiers to Santa Fe to explain their “business on his frontier.”

After securing promises that the Spanish would assist the men of his party still absent from the stockade, Pike assented to accompany the New Mexicans back to Santa Fe. He and his men had exchanged their avocations from explorers, to the uncertain status of official “guests” of the Spanish government.

![Introducing the General Zebulon Montgomery Pike INTERNational Historic Trail [ZPIT]](https://www.zebulonpike.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/21-St-Anthony-Falls-144dpi-wm-150x150.jpg)