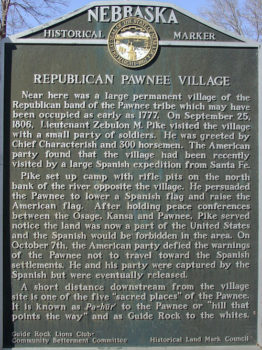

Zebulon Montgomery Pike spent little time in what is now Nebraska during his 1806-1807 exploring expedition to the American Southwest, but his visit to the Pawnee Village on the Republican River was one of the most important parts of his trip. It was a brief but significant interlude in his trip across Kansas, and there was for a time debate among scholars as to whether the village site was actually located in modern-day Kansas, or Nebraska. General James Wilkinson, who sent Pike on his expedition, directed Pike to visit the Pawnees, seek to make peace between the Pawnees and other tribes, and request assistance from the Pawnees in the form of guides and interpreters in order to make favorable contacts with the Comanches on the Great Plains. What Pike did not know or suspect was that a large Spanish expedition, comprised of some 400 troops led by Lieutenant Facundo Melgares, had visited the Pawnee Village a few weeks prior to his arrival.

Pawnee Village Sign

The Pawnees had, after the removal of the French from the region following the Treaty of Paris in 1763, become part of the Spanish trading empire, and within a few years Pawnees were making annual expeditions to New Mexico to trade with Spanish and Pueblo peoples. Spanish officials in northern Mexico considered the Pawnees to be their allies, although they feared the United States was attempting to win the trade and support of the tribe. Thus, Melgares and his troops were sent to impress the Pawnees and to attempt to find and capture the Lewis and Clark expedition on the Missouri River. The Pawnees may have been impressed with the size of Melgares’s army, but they did not show many signs of cooperation. They apparently understood at this point they could play off the Spanish and U.S. officials to their own advantage. For whatever reason, they prevented Melgares from proceeding on that portion of his mission to find Lewis and Clark. The Spanish troops returned to New Mexico, their mission considered to have failed.

Prior to Pike’s arrival, Melgares visited the Pawnee Village and left presents and a Spanish flag with the leaders of the village and requested that they prevent anyone from the United States from proceeding farther west and southwest toward Spanish settlements. Pike encountered that opposition.

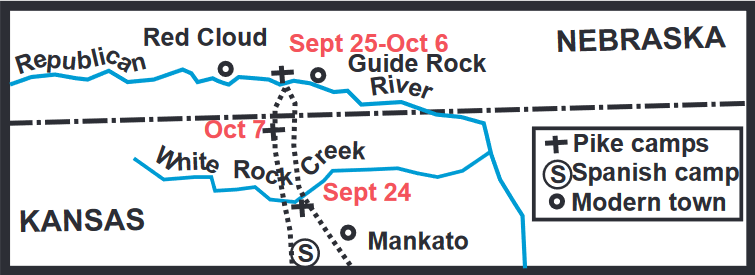

Pike and his party of 23 men camped near the Pawnee Village, which was located on the Republican River between the present towns of Red Cloud and Guide Rock. They arrived on September 25, 1806, and spent nearly two weeks there, departing on October 7. It was here that Pike learned about Lieutenant Melgares and his troops, and he found that the Pawnees had hung up a Spanish flag recently given them by Melgares. What followed is recorded in Pike’s journal:

29th September, Monday.—“Held our grand council with the Pawnees, at which were present not less than 400 warriors, the circumstances of which were extremely interesting. The notes I took on my grand council held with the Pawnee nation were seized by the Spanish government, together with all my speeches to the different nations. But it may be interesting to observe here (in case they should never be returned) that the Spaniards had left several of their flags in the village; one of which was unfurled at the chief’s door the day of the grand council, and that amongst various demands and charges I gave to them, was, that the said flag should be delivered to me, and one of the United States’ flags be received and hoisted in its place. This probably was carrying the pride of nations a little too far, as there had so lately been a large force of Spanish cavalry at the village, which had made a great impression on the minds of the young men, as to their power, consequence, &c. which my appearance with 20 infantry was by no means calculated to remove. After the chiefs had replied to various parts of my discourse, but were silent as to the flag, I again reiterated the demand for the flag, “adding that it was impossible for the nation to have two fathers; that they must either be the children of the Spaniards or acknowledge their American father.

After a silence of some time, an old man rose, went to the door, and took down the Spanish flag, and brought it and laid it at my feet, and then received the American flag and elevated it on the staff, which had lately borne the standard of his Catholic majesty.This gave great satisfaction to the Osage and Kans, both of whom, decidedly avow themselves to be under the American protection. Perceiving that every face in the council was clouded with sorrow, as if some great national calamity was about to befal them, I took up the contested colors, and told them “that as they had now shewn themselves dutiful children in acknowledging their great American father, I did not wish to embarrass them with the Spaniards, for it was the wish of the Americans that their red brethren should remain peaceably around their own fires, and not embroil themselves in any disputes between the white people: and that for fear the Spaniards might return there in force again, I returned them their flag, but with an injunction that it should never be hoisted during our stay. At this there was a general shout of applause and the charge particularly attended to.”

The Pawnees accommodated Pike, but were unwilling to help him go farther, honoring the request of Melgares to stop the advance of people from the United States. The chiefs also indicated their own opposition to Pike pushing on to meet with the Comanches, their enemies, and seek the headwaters of the Arkansas River. They informed Pike that they did not intend to allow him to proceed on his expedition and would, if necessary, as Pike recorded, “stop us by force of arms.”

You can find this painting at the Pawnee Indian Village Museum near Republic, KS, operated by the Kansas State Historical Society. The painting, titled “Uncertain Welcome” by Darrell Combs, represents the Pawnees meeting Pike’s command at the Pawnee village near Guide Rock, Nebraska.

Pike explained he was on a mission for the “great father” and said his party would not be turned back. His soldiers were not women but men, who would willingly fight to the end. General Wilkinson had ordered Pike to meet with the Comanches and “no pains must be spared to effect it.” Pike made it clear, although outnumbered by Pawnee warriors, his small band of soldiers would fight if necessary, taking as many lives as possible before they were killed. Pike also warned them that U.S. troops would come in large numbers to avenge the deaths of his troops, should the Pawnees destroy them.

After consideration of Pike’s strong statements, the Pawnees relented. Pike then purchased some horses from them and made preparations to move on. While at the village, Pike met two French traders who informed him that Lewis and Clark and their party were descending the Missouri River. This was good news to the expedition.

On October 7, Pike was prepared for the worst because of Pawnee threats to prevent his pushing on, and he recorded their departure from Nebraska in his journal:

“…We marched at two P. M. and as the chief had threatened to stop us by force of arms, we had made every arrangement to make him pay as dear for the attempt as possible. The party was kept compact, and marched on by a road round the village, in order that if attacked the savages would not have their houses to fly to for cover. I had given orders not to fire until within five or six paces, and then to charge with the bayonet and saber, when I believe it would have cost them at least 100 men to have exterminated us (which would have been necessary) the village appeared all to be in motion. I galloped up to the lodge of the chief, attended by my interpreter and one soldier, but soon saw there was no serious attempt to be made, although many young men were walking about with their bows, arows, guns and lances.”

Pike had obtained supplies and information from the Pawnees that aided his pursuit of his major missions, to find the sources of the Arkansas and Red rivers, but received no help in finding the Comanches, whom he never met. Not meeting the Comanches was one reason Wilkinson considered Pike’s expedition a failure.

Pike’s stay in present Nebraska was brief, but what happened there was an important part of his expedition. Relations between the Osage and Kansa tribes improved, and both engaged in trade with the United States. Soon the Pawnees were converted from their trade alliance with the Spanish and came into the sphere of traders from the U.S. In later years the Pawnees became allies of the United States and helped fight against other more hostile tribes on the Great Plains.

Pike re-entered Kansas and followed the “Spanish Trace” of Melgares to join the Arkansas River and continue his quest for its source. Although Nebraska had provided some tense moments, Pike’s dramatic ventures had just begun.

![Introducing the General Zebulon Montgomery Pike INTERNational Historic Trail [ZPIT]](https://www.zebulonpike.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/21-St-Anthony-Falls-144dpi-wm-150x150.jpg)