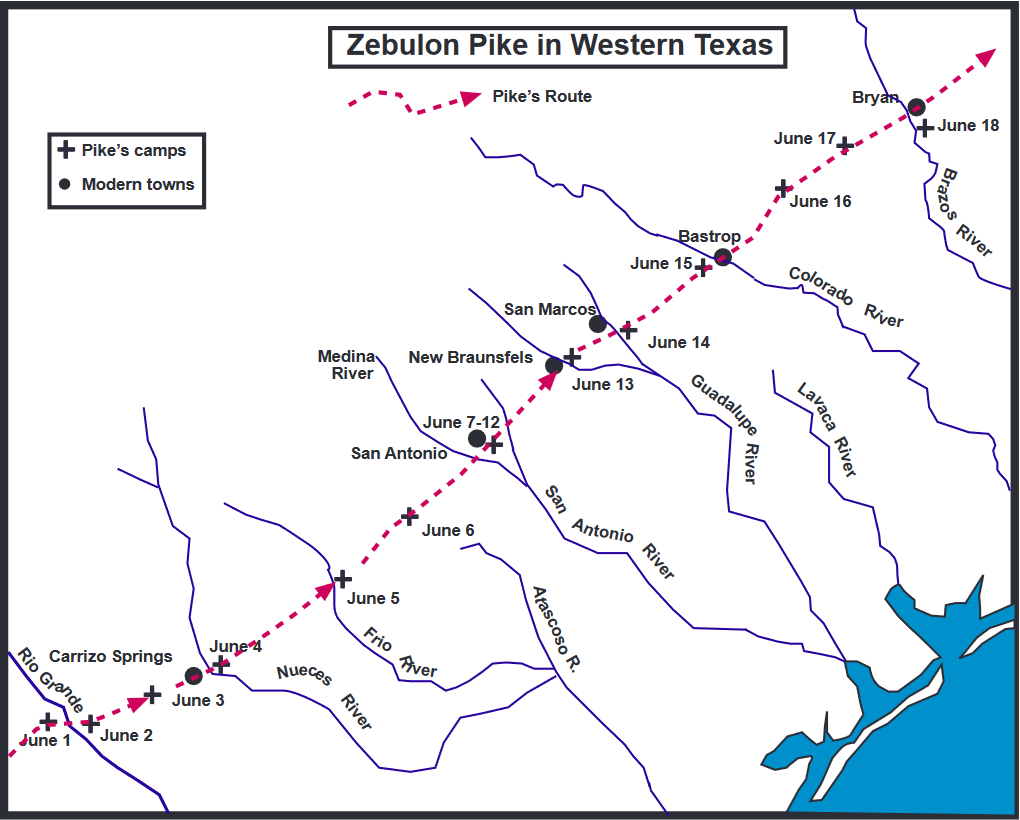

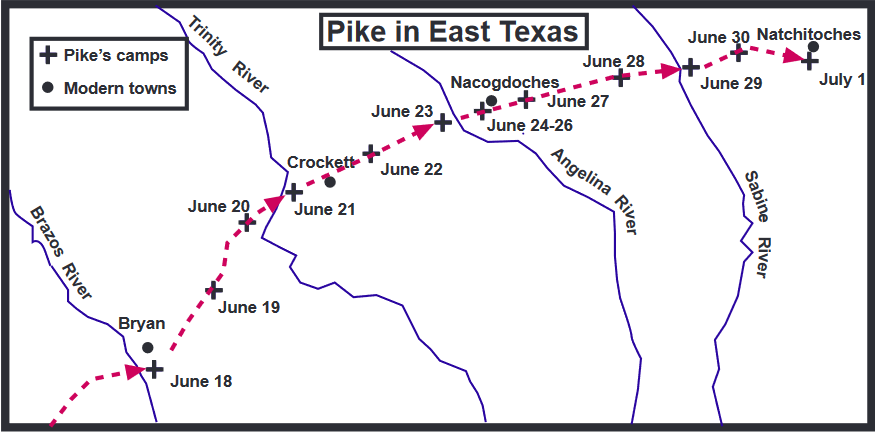

As lieutenant Zebulon Pike splashed across the Rio Grande River and into what would become the modern state of Texas in early June of 1807 his luck—or lack of it—had been an ongoing question since the unexpected turn of events many miles upstream of the same river the previous February.

An important aim of Pike’s original mission had been to locate the headwaters of the Red River, and follow it back to the U.S. military post at Natchitoches, Louisiana. This would allow Pike’s expedition to explore what was ostensibly the boundary between Spanish Texas and the U.S. territory acquired under the Louisiana Purchase, and given the 1806-1807 hardships of their mid-winter travails in the Rocky Mountains, bring their mission to a mostly successful conclusion.

Instead, Pike and his party were not skirting Texas, but on a journey through the very heart of it. They were being expelled from Spanish territory under the watchful eyes of an escort of Spanish dragoons, nearly as far from the Red as geographically possible, and under a cloud of suspicion by their captors that they had been on a mission of espionage. Ironically, the destination of the U.S. military post that the Spanish chose to expel the interlopers at was Natchitoches, and equally ironic was the fact that if the Pike expedition actually had been a state-sponsored espionage mission to reconnoiter northern New Spain, there was little more the Spanish could have done to facilitate its success than they had already done since his capture.

Although the Americans were suspected of being spies, Spanish authorities had uncovered little physical evidence to corroborate it, and it had been problematic to disprove the simple fact that the expedition had mistakenly wandered into Spanish territory in a desperate bid to escape the dire winter conditions in the mountain valleys of southern Colorado. Hauled to Santa Fe after their initial capture, indecisive Spanish authorities in New Mexico sent their unwelcome guests south under military escort to Chihuahua and yet higher authorities, who were the ones who made the decision to expel Pike from their territory via Texas. In doing so, they inadvertently bestowed upon Pike, an alert and observant officer, a golden opportunity to experience a firsthand view of the very things that the Spanish had heretofore made earnest attempts to mask from its expansionist U.S. neighbor: a detailed portrait of the people, resources, and landscapes of a significant slice of their adjacent northern territories. Half-prisoners and half guests, thanks to the Spanish themselves, Pike scored an intelligence coup that would be the envy of any premeditated state-sponsored espionage mission.

The Spanish were not unaware of the value of such detailed intelligence for their U.S. neighbors, and so had relieved Pike of portions of his expedition notes after his capture. Problematic, however, was how they could prevent the ever-observant and resourceful Lieutenant (or members of his command) from gathering and logging any detailed observations of the sort that was bound to present itself on the lengthy journey from Chihuahua to Natchitoches. Pike was specifically warned by the authorities before departure that he was forbidden to take notes or take any navigational bearings during the trip, and his Spanish companions tried as best as possible to keep an eye on him, but it proved a cat-and-mouse game at times, and Lt. Pike proved a worthy and resourceful mouse. He established a routine, for instance, where he would find an excuse somewhere on the daily march to find a “pretext to halt,” and then repair to the privacy of some bushes to screen his activities from Spanish eyes while he jotted down field notes on the sly. To prevent the discovery and almost certain confiscation of his forbidden handywork, he distributed the completed log pages among his men, who secreted them in their clothes, or even rolled them into tight cylinders and tapped them down the barrels of their large-caliber smoothbore muskets. While this strategy proved quite successful throughout the entire journey, the Spanish weren’t entirely unsuccessful in thwarting some of Pike’s clandestine intel-gathering. Pike had specifically been warned against taking any formal navigational measurements, but had been able to retain a compass as part of his personal kit. Pike’s journal reveals that he had used the compass for setting his watch during the journey, but it doesn’t take much imagination to surmise that he used it surreptitiously for directional readings. He also noted that the instrument had attracted the attention of his Spanish escort, who had expressed their “dissatisfaction” at his use of it. It should have come as no surprise, then, that when the U.S.-Spanish contingent crossed the Rio Grande on the second day of June 1807, it was without Pike’s compass. It had mysteriously gone missing that day when his back was turned.

After the numerous miles of arid country that the detail had passed through since their departure from Chihuahua, today’s Texas landscape, and its flora and fauna, increasingly filled the pages of Pike’s clandestine trail journal. The day after the compass disappeared, he recorded being treated to the first glimpse of what would be a growing presence of the wild mustangs that swarmed the Texas plains—as well as growing swarms of a less romantic member of the region’s fauna, the Texas mosquito. Even the first appearance of that travelling companion of the Texas mustang, the Texas horsefly, made its debut in his logbook on that day. On June 6, he recorded seeing the first “wood land” that they had seen since departing Osage country in eastern Kansas. That same day, another iconic Texas resident, the pig-like javelina, scored an entry in his journal.

Although the party had been in today’s Texas since the Rio Grande, on June 7, they crossed Medina River, which Pike noted as the boundary line between the provinces of Coahuila and Texas. As they were now angling across Texas on the well-established Camino Real de los Tejas, they drew ever closer to the most populous part of the province and its principal political center, San Antonio, then known as San Antonio de Béxar, and to Pike as “Saint Antonio.” Spanish-U.S. border issues along the Sabine River boundary had served as a source of ongoing tension between the two nations, to the point where a year before Pike’s arrival, they had almost come to blows. Even as the Americans and their escort closed in on San Antonio, a detachment of troops under the former governor of Nuevo León, Simón de Herrera, was still stationed in Texas to bolster Texas governor Antonio Cordero in case of more border trouble. The appearance of a detachment of U.S. soldiers under suspicion of spying on Spain could well have been met with a very ambivalent welcome.

Instead, Pike recorded that Cordero and Herrera received the ragged Americans “like their children.” That evening, a public ball, or bailé, was held for them in the main square of town, followed by a week of banquets, sightseeing, and socializing. Pike characterized Cordero and Herrera as men of “super-excellent qualities,” and was impressed by their character, generosity, and their impressive knowledge of U.S. political and social institutions.

The Americans and their Spanish escort left San Antonio on June 14, and headed east toward the town of Nacogdoches, where they spent June 24-26 being entertained, and meeting a variety of locals, including some American businessmen. As they marched ever eastward, the evidence of a polyglot U.S.-Spanish borderland culture increased: escaped Louisiana plantation slaves, French and Irish frontiersmen, mule trains, groups of local Indians, and scattered settler homes came and went along the route as U.S. territory drew ever closer.

On June 29, nearly a year after the expedition began its mission, Pike and his command bid farewell to their Spanish escort, and crossed the Sabine River into U.S. territory. Their first house call on American citizenry turned out to be a cabin full of would-be smugglers. On June 30, at 4:00pm, the saga of the Pike expedition drew to a close as they entered Natchitoches.

Like Lewis and Clark, Pike is a key figure in the nineteenth-century history of American expansion. His subsequent report, both of his endeavors before and after his capture by the Spanish, revealed vital information on the geography, culture, and ecology of the regions he explored, much of which was hidden from the American public or its policymakers behind the concerted effort of the Spanish government to screen it from the gaze of what they perceived to be their acquisitive U.S. neighbor.

While Pike’s capture by the Spanish largely cut short his government-mandated exploration mission, it also opened up significant opportunities for “exploration” to which Pike was to have equal if in some aspects even more significant contributions to U.S. policy and subsequent strategies. One of Pike’s strengths was his ability as a keen observer of the human condition, and his interpersonal skills vis-à-vis his predicament as a Spanish prisoner. Although technically a captive of the Spanish, Pike showed a remarkable ability to easily make the best of his situation, and through the foibles of his captors, was literally given a grand tour of a great chunk of northern New Spain. Although in many ways a product of his time with regard to social mores and the political exceptionalism of American society, Pike’s interpersonal skills, as well as his relatively open mind, made him a keen and relatively non-biased observer of both the geographical layout of his captors’ territory, as well as the social and political mindset of its inhabitants, who were more than willing to share their views and customs with him. When finally escorted out of Spanish territory, his expedition report, which soon circulated among the American public, painted what became one of the most comprehensive and influential pictures of its time of the resources, geography, and mindset of America’s Spanish neighbors. It painted a picture of the vast prairies of a Texas teeming with wild horses, of political dissent simmering below the surface among some segments of the Spanish population, of Spanish citizens, good and bad, but not so unlike their American neighbors, of opportunity to those Americans who saw Spanish territory as a future target for expansion, a harbinger of Manifest Destiny.

![Introducing the General Zebulon Montgomery Pike INTERNational Historic Trail [ZPIT]](https://www.zebulonpike.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/21-St-Anthony-Falls-144dpi-wm-150x150.jpg)